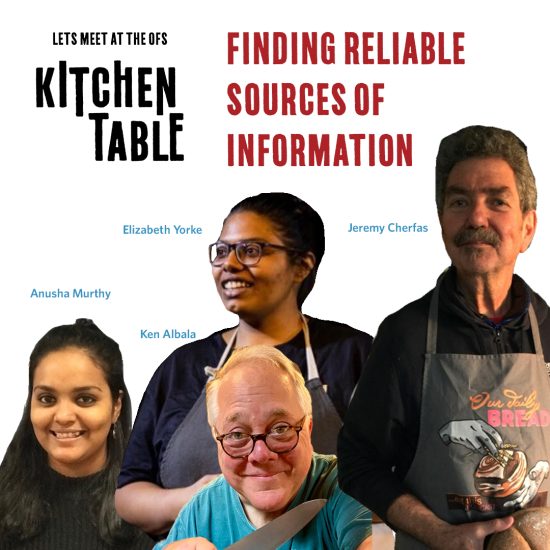

We need to talk about… how to find reliable sources of information when writing about food – a digest from the chatline

At the last official Kitchen Table before the Symposium, trustee-director Ursula Heinzelmann led a wide-ranging discussion on how to avoid fake news in the food world at a time of information-overload. Joining her at table were biologist Jeremy Cherfas (Eat This Podcast), historian Ken Albala (Food: A Cultural Culinary History), engineer Anusha Murthy (Edible Issues), and chef Elizabeth York (Edible Issues).

WHO AND WHAT CAN WE TRUST?

Gold dust or fool’s gold? To know if a story makes sense you have to have some basic knowledge of subject and context. For instance, wheat exports from Ukraine represent 30% of the world’s wheat exports rather thanproduction, as the statistic is sometime presented. Categorizing cows as climate-killers is another misinterpretation of reality. The stakes are even higher when misinformation is used against specific groups.

Press statements are often unsubstantiated and have no references. Much of what we’ve been hearing is about clearly rubbish, but when there are credible arguments on both sides, it’s much harder to make judgements. For example, is raising calves for veal cruel? Is wild fish better than farmed? Should the EU have banned so many products during the “Mad Cow” crisis?

One should always question statistics, ask what’s being measured and what’s the denominator. As for the creation of specific visual content to convey misinformation, can it ever be possible to get to the source of those files that are profusely shared on certain channels?

WHAT’S DO WE MEAN BY AUTHENTİCİTY?

It’s just one person’s word on what is authentic. [To get an idea] I talk to friends from different regions of India: they all have contradicting versions of authenticity. Take Parsee cooking: people have moved around so much that relating a recipe to a person makes it as original and authentic as it can possibly be. Authentic food sometimes evolves into something that’s not at all delicious.

In some cultures, the recipe for a particular food item varies from neighborhood to neighborhood in the same town, and therefore, one may come across over 10 different “reliable” recipes for the same food items.

Food is like species, constantly evolving over time – like giraffes.

[There’s an idea that people won’t tell you their secret ingredient and hold something back]. Julian Barnes talks about missing ingredients in Jane Grigson’s recipes in The Pedant in the KitchenI think people thinking someone left out an ingredient is like asking a great pianist for a copy of the Chopin piece just played and thinking notes were left out because it doesn’t sound the same at home.

There’s no such thing as the perfect recipe. A lemon-drizzle cake cooked competitively from the same recipe by different people for a Women’s Institute bake-off doesn’t produce identical results.

CAN WE TRUST THE PRINTED WORD?

The great temptation is to work with cookbooks and print sources. The written word has such terrific power! Think of the way the OED, for example, privileges first printed use. Books can have significant typographical errors that mislead about the recipe; or can lead to outright intellectual property theft.

When studying Persian cookery, [I found that] many source documents, including handwritten transcripts, are not accessible and/or have not been transcribed and/or translated.

As a librarian, [I can say that] libraries are much more than books: ask your librarian for help with research.

Paul Freedman wrote eloquently in his book “Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination (2008)” about the fallacy that spices were used to disguise bad meat. He talks about the presence of fresh meat, the cost of spices.

CAN WE TRUST THE SPOKEN WORD?

People want their stories to be true. The story is not the same as the recipe, which is written down long afterwards. Stories get repeated on and on till the original story disappears.

There’s such a thing as “fakelore”.

The English word “sourdough” gives the wrong impression. “Sourdough” suggests the bread tastes really sour, which is not the goal, except for some people who are really trying to make super-sour bread. “Pain au Levain” gives the right impression, says that this is wild yeast.

CAN WE TRUST THE INTERNET?

As a teacher, I have to deal with students going on-line and picking up stuff that’s not true.

How can you deal with the fact that many of the online sources are behind pay walls? As a researcher not affiliated with a university, there are many sources I cannot access without either the university affiliation or excessive fees. Or even with university affiliation, much is inaccessible because too expensive: a case in point is EEBO (Early English Books Online).

On Google, paywalled sources are often higher in the results than say, resources at the Library of Congress. The second google page is often pretty useful! It’s a running joke that the best place to hide a dead body is the second page of Google.

SO WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

Why does it matter to be right or wrong? Why do people care about the authenticity of a recipe? The simple answer is that the pizza makers of Naples, who got their recipe enacted into EU law, certainly do.

Doesn’t it also depend on what the goal is? Are you trying to win an argument and prove yourself “right”? Or do you just want to document a particular viewpoint or storyline?. Food-romances and myths can also be useful and natural even when not accurate: they create enthusiasm, help people think in categories.

As Ruth Reichl said in a previous symposium on Food & Morality: “People want to do the right thing, but it’s just so hard to know what that is.”

CONCLUSION: There’s no such thing as one single truth.