Report by Josh Evans

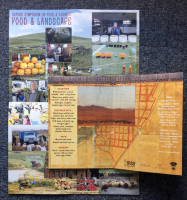

Though ‘Food and Landscape’ had been anticipated to be a popular theme, the response was overwhelming. Not only were 178 paper-proposals submitted for 42 available slots, but 40% of us were attending for the very first time. And, in addition to the official programme, there were two pre-symposium satellite events—a Wiki-editathon designed to boost the number of Wikipedia entries related (not only) to women and food, and a viewing of food-related objects from Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum as part of Symposiast Linda Roodenburg’s Oxford Food & Museum Project.

So even before the Symposium began, the air at St. Catz was filled with excitement. Claudia Roden, Bee Wilson, and Ursula Heinzelmann offered opening remarks to the packed lecture hall, with particular warmth for the sizeable contingent of first-timers and higher-than-ever-before number of student Symposiasts. Thirty-nine students joined us, up from twenty-nine last year, and we look forward to seeing even more young scholars join the Symposium in years to come.

Bee then introduced the first plenary speaker of the weekend, biologist, author and broadcaster Colin Tudge. Colin made a powerful case for ‘enlightened agriculture’, a combination of agro-ecology, food sovereignty and economic democracy that would transform the agricultural landscape. He finished by reflecting on the strong connections between agriculture, nutrition and gastronomy, sketching out broad themes for the weekend to come. Culinary historian Catherine Brown followed up Colin’s talk with this year’s Jane Grigson Memorial Lecture by providing an overview of the food and drink heritage of Scotland’s ‘Challenging Landscape’.

Where Colin’s talk was a call to arms, Catherine’s was a reflection on the importance of subjective experience and memory. Reminiscences learning at first hand how to prepare venison haggis, stag’s head broth, and fish liver pudding expanded into a history of the depopulation of the highlands and islands during the Clearances, and their more recent and heartening repopulation. The connections between the two talks were clear: as Catherine reminded us, ‘talking to old people with old memories’ can be a powerful way to inform and encourage the kind of enlightened agriculture Colin envisions for the future.

The Celtic connection continued with The Boyne Valley Banquet, a celebration of the very best of Ireland’s Ancient East, organised by Trustee Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire and sponsored by Fáilte Ireland. The fruit of many hands and hearts, the feast outdid all expectations, even for the Symposium. Perry still fizzed on our tongues from the outdoor reception as we tucked into boards piled high with oysters, smoked salmon and charcuterie, followed by beef in many guises: three different cuts of roast, ‘tongue ‘n’ cheek’ pie, and enormous platters of beef stew cooked in a cauldron over slow-burning peat. Rainbow plates of veg, far from an afterthought, lent bursts of colour and refreshing flavours to the meats.

All this we washed down in true Irish style with various beers and ciders, as well as 2012 Château Mauvesin-Barton from Moulis-en-Médoc, a reminder of the Irish wine diaspora, the so-called ‘wine geese’ that have been playing in claret’s first league since the late seventeenth century. Dessert, a sorbet of Lannléire honey, came with a not-so-wee dram of Irish whiskey or a tipple of cream liquor. After dinner, the choice lay between an introduction to founding-Symposiast Barbara Wheaton’s magnum opus, ‘The Sifter’, a database designed to facilitate the digital search and use of historical cookbooks, or a continuation of Irish merriment with a convivial tasting of beers, braggot, and whiskey interspersed with songs and collaborative story-telling from the Emerald Isle.

Come morning, the lecture hall again was thronging with Symposiasts eager to hear James Rebanks, author of The Shepherd’s Life, Oxford graduate and descendent of 600 years of shepherding in the Lake District. James spoke concretely to the realities of family life and livelihood as a hill-farmer rearing Herdwick sheep in a World Heritage landscape—an apt illustration of Colin Tudge’s concern over the economics of industrial production.

After the coffee break, Máirtín and Ursula shared news of the work of the Friends and American Friends of the Oxford Symposium this past year—digitising proceedings, publishing videos of last year’s talks, producing a new podcast, and many more projects that enrich the Symposium community throughout the year. They also introduced the recipients of the two Young Chef Grants, Deborah Ryan from Ireland and Girish Nayak from India, who had joined Tim Kelsey and the St. Catz team working with the Irish chefs on Friday evening and thereafter joined us in the Symposium’s sessions.

Later that morning, a panel discussion between Claudia Roden, Elisabeth Luard and Naomi Duguid as well as food activist Joshna Maharaj took as its point of departure an oft-cited quote (and favourite of Claudia’s) from Catalan historian Josep Pla: ‘Cuisine is the landscape in a saucepan’—an apt by-line for the whole Symposium. I was particularly moved by how their discussion framed Joshna’s presentation of her work in transforming the physical, social, and culinary institutional landscapes of some of Toronto’s hospitals and universities. Joshna talked about landscape as ‘a space structured by priorities’, which allowed her to draw surprising connections between the transformations she sparked in the kitchens, patients’ rooms, dining halls, and rooftop farms of the institutions she worked to enrich.

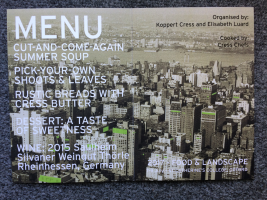

The rest of the day was filled with a wide range of paper-presentations, from Japanese rice-paddy art and Oaxacan tejate to an historical explanation for the puzzling lack of American taste for their own wine despite their grape-hospitable landscapes. Connections were made between farming methods, milk biodiversity and cheese quality, and a theory was presented on how the olive-line, date-line, and grape-line shaped Mediterranean culture. Midway through the day, lunch was served on tables transformed by Dutch growers of micro-greens, Koppert Cress, into an urban landscape of miniature garden-plots. Armed with our hands and the occasional pair of scissors, we tasted our way through a dozen varieties of cresses, leaves and aromatic herbs to round out a smooth gazpacho, garlic toasts, ceviche and salads. In our glasses was a white wine whose aromas matched all the leaves and herbs, a Silvaner from the Rhine-bordering region of Rheinhessen in central Germany, grown by the renowned Thörle family.

The light lunch helped our appetites return in the time for Saturday’s supper, a culinary tribute to the contested borderlands of Armenia and Turkey. Organised by Gamze İneceli and İhsan Karayazı in association with the Culinary Arts Academy of Istanbul, the menu highlighted the shared culinary traditions of a common landscape split by political strife. The evening began with a reception in the garden sampling Turkish wines, Armenian apricot brandy, and an astounding variety of Anatolian olives—black to yellow, purple to green, hazelnut-sized to the heft of a small plum—along with a book-signing by Naomi Duguid of her remarkable Taste of Persia: A Cook’s Travels in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran and Kurdistan, and my own On Eating Insects, as well as a sale in aid of Friends of the Oxford Symposium of long-time Symposiast Sri Owen’s library of cookbooks.

Inside the hall, the feast began in earnest. Dishes flew out of the kitchen and were emptied just as quickly: aubergine with smoked yogurt; pickled beetroot, walnuts and çeçil string cheese; bean puree and pastırma; stuffed chard leaves with emmer and sour cherries; braised lamb shank (which, in another overcoming of borders, came from Scotland) with jewelled rice; and finally kavut, toasted wheat halva with apricots and milk ice cream. The delicious wines made from indigenous grape varieties also bridged the Armenian–Turkish border, from Kayra in Turkey and Zorah in Armenia. After dinner, Symposiasts were invited to inspect and help themselves to Tasha Mark’s edible art-installation, an intricately sculpted landscape of dried fruit and nuts. Meanwhile, the documentary film that inspired the meal was shown—the story of a spontaneous collaboration between two groups of village women without a common language cooking together on both sides of the Armenian–Turkish border.

Nicola Twilley kicked off Sunday with a vivid and inspiring explanation of the concept of ‘Aeroir’, the result of her research into variations in smog quality across several major cities, which then led to a collaboration on building a machine to recreate the aromatic profiles of different smogs and use them to make meringues suitable for tasting. The project might have appeared frivolous to some, Nicola told us, but as soon as people tasted the meringues the idea of Aeroir became a powerful tool for opening up thoughtful and visceral discussions about air-pollution, health, and the taste of place.

In two short plenary talks before lunch, Inigo Thomas reflected on different senses of time in the landscape of the western Mediterranean peasant kitchen, and I reviewed some recent scientific and gastronomic research on microbial landscapes in food fermentation.

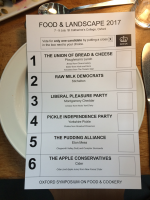

Lunch, organised by Trustee David Matchett with generous contributions from London’s Borough Market, was a rustic and satisfying affair of sourdough bread, cultured butter, pickles, excellent sparkling cider and two of England’s most renowned raw milk cheeses, Montgomery Cheddar and blue-veined Stichelton, with the atmosphere in the hall enhanced by a sound-installation recorded in Borough Market a few days earlier by electronic producer and composer Ben Houge. I felt camaraderie bubbling in the air as Symposiasts, saturated with a weekend’s worth of ideas, tastes, memories and friends, tucked in with their hands and broke bread with companions old and new.

After the afternoon’s final sessions, everyone reconvened in the main lecture theatre to applaud recipients of awards for outstanding presentations and student papers, followed by what was described as the ‘joyfully chaotic selection’ of our theme for 2020. After an uncharacteristically orderly process of reading out all subject-suggestions collected over the weekend and narrowing them down to a final list, the decision was reached that 2020 shall explore all things Herbs & Spices. And with that, the 2017 Symposium came to a close.

Plenary sessions

Keynotes

Claudia Roden, Elisabeth Luard, Joshna Maharaj

Colin Tudge

James Rebanks

Nicola Twilley

Inigo Thomas

Joshua Evans

Catherine Brown

Awardees

OFS Young Chefs

Deborah Ryan, Girish Nayak

Cherwell Prize

Casey Ireland

Meals

Friday Dinner

Boyne Valley Banquet

Organised by – Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire.

Sponsored by – Fáilte Ireland, Irelands Ancient East, the Boyne Valley Food Series.

Thanks to – Rob Krawczyk, Ryan Mc Givern, Dearbhlá Moriarty, Mairead Farrell, Olivia Duff, Helen Byrne, Padraic Og Gallagher, Boyne Valley Food Series, Donegans of Monasterboice , Mullagha Farm Cheese, Drummond House Garlic, The Wooded Pig, Newgrange Gold, Ballymakenny Farm, Kerrigan’s Mushrooms, Carlingford Oysters, Martry Mill, Dunany Flour, Hilda’s Homemade Garden Chutneys, Sheridans Cheesemongers , Bellingham Blue Cheese, Lannliere Honey , Coastguard Seafood, Oriel Sea Salt , Boyne Brewhouse , Sally Anne Cooney, Slane Irish Whiskey, Coole Swan Irish Cream Liqueur, Listoke Irish Gin, The Cider Mill, Dan Kelly’s Cider.

Cooked by –Rob Krawczyk, and Tim Kelsey and St Catz staff.

Saturday Lunch

The New Koppert Cress Tasting Menu, The Undercover Gardener

Organised by – Koppert Cress and Elisabeth Luard.

Sponsored by – Koppert Cress B.V.

Thanks to – Paul Da Costa Greaves, Franck Pontais, Jak Cresser-Brown, George Johnson, Weingut Thörle, Ultracomida.

Cooked by – Cress Chefs.

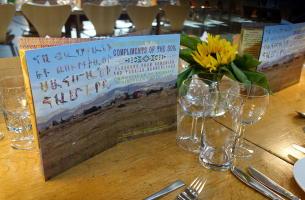

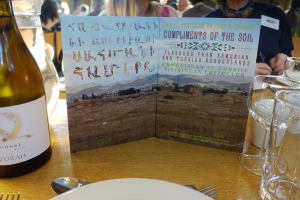

Saturday Dinner

Compliments of the Soil, Flavours from Armenian and Turkish Borderlands

Organised by – Gamze Ineceli, Ihsan Karayazı, Ursula Heinzelmann.

Cooked by – MSA The Culinary Arts Academy, Instanbul, & Tim Kelsey and St Catz staff.

Sponsored by – MSA The Culinary Arts Academy, Instanbul.

Thanks to – MSA The Culinary Arts Academy, Scotch Lamb, Kayra Wines, Zorah Wines.

Sunday Lunch

Ploughman’s Lunch – An Aural Reconstruction by Ben Houge and David Matchett

Organised by – Elisabeth Luard and David Matchett.

Sponsored by – Borough Market.

Thanks to – Bread Ahead, Trustees of Borough Market, New Forest Cider, Oliver’s Bakery, Rosebud Preserves, Neal’s Yard Dairy, The Tomato Stall, Gourmet Goat, Hook and Sons, The Turkish Deli.