Report by Len Fisher

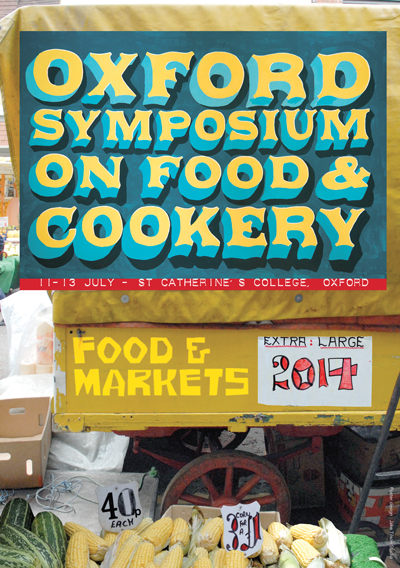

This year’s Symposium was one of the most successful ever in terms of the quality and range of the talks, the meals, as well as the welcome presence of many new symposiasts, who constituted some 40% of the total. First-timers were identified by green badges, while repeat offenders were identified by more sombre black, or red if they were trustees. This made it very easy to initiate conversations, and conversation is what the symposium is largely about – along, of course, with the papers and the food.

Here I present a personal selection from the many highlights, as experienced by me or told to me by others, with apologies to the many excellent speakers whose talks are not mentioned, but whose input and ideas will not be forgotten by those who were present.

The Papers

The symposium got off to a flying start with Darina Allen’s (of Ballymaloe Cookery School fame) vivid account of the establishment of a network of farmers’ markets in Ireland, for which she has largely been responsible. Her enthusiasm and drive, together with her bluff responses to the sometimes unthinking demands of the regulatory authorities (e.g. demanding running hot and cold water for hand washing) held the audience breathless (in this case, her common sense answer was for stallholders to bring a thermos of hot water and a bottle of cold water!).

Award-winning author Anya von Bremzen (“Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking”) delivered the second plenary, with her personal and sometimes grim memories of a childhood in Soviet Russia, where food was used a political weapon and trawling the black market for delicacies, or even basics, was fraught with danger. In a following parallel session, Irina Rutsinskaya and Galina Smirnova showed how this situation was depicted in art, both during and after the Soviet period.

The third plenary lecture, on the fate of leftovers from the royal table in eighteenth-century France, delivered by Janet Beizer with her usual mixture of dry wit and scholarly precision, was a major highlight of the symposium. She showed how leftovers were formed by sellers into “Arlequins” – a patchwork mixture (like the patchwork of a Commedia dell’arte Harlequin costume) that could contain just about anything. With considerable relish she demonstrated just what they could contain, producing from a large cast iron pot fish heads, crab shells, half-eaten tarts, meat bones and a host of other ingredients that went through stages of sale and resale, gradually rotting and getting cheaper, and sometimes even rescued from refuse heaps after the authorities had confiscated and dumped them.

A highlight of a different kind was provided by the award of the Sophie Coe Prize in Food History to Garritt Van Dyk for his highly original and fascinating study on the origins of champagne. Van Dyk’s article combined the twists and turns of a detective story with thorough and deep research to reach a startling conclusion – that British knowledge of techniques for capturing effervescence in the manufacture of cider and perry was vital to the creation of champagne, even though the invention of champagne was subsequently appropriated by the French and attributed to the Benedictine monk Dom Pérignon.

While on the subject of prizes, congratulations must go to Mary Gray, whose talk “Food and the Female Body” drew interesting parallels between the food market and the prostitution market in Fanny Hill, and deservedly won the award for best student presentation. There were interesting connections between this and Janet Beizer’s talk, and also that of Gillian Riley, who gave us a guided tour of pictures featuring food from Southern Italy that had finally found its way to the North, painted by Dutch artists. She always seemed to find something of interest in the background – a bible scene on one side, something rather more lascivious on the other – and her tongue-in-cheek account frequently had the audience in stitches.

Gillian’s was one of many talks in the parallel sessions that grabbed the audience’s attention and held it. Many symposiasts commented on the quality and interest of a session with the unexpected theme of violence. Volker Bach talked about supplying armies in sixteenth-century Germany, followed by David Sutton talking about rioters and regulators in Georgian England, with both speakers bringing their themes alive in a way that we used to hope for, and have now come to expect, at the symposium.

Andrew Coe’s talk on the kosher poultry racket in early twentieth-century New York was another that drew wide-spread comment, and held the audience enthralled with its account of how employers and labourers alike used gangsters to get their way and defeat their rivals.

Room D, with its weird (but true to historical original designed by Arne Jacobsen) arrangement of chairs and tables around an empty central area, was frequently filled to capacity, never more so than in the session featuring Doug Duda and Dan Strehl, where there were many more standees than there were sitters. Doug’s was one of the few to ask “why?” in his talk about why markets grow while cooking crashes. He made the particularly valid point, reflected by a few other speakers, that despite the enthusiasm and public approval for farmers’ markets, they still account for less than one percent of food sales, and major supermarkets are having an impact even here, especially in the sale of “organic” foods.

Dan’s sometimes ironic account of the sights and sounds of the Hollywood market, just one block from the famous Hollywood and Vine intersection, contained a valuable lesson – that regulation can sometimes be beneficial to the small producer. In this case, the farmer must obtain a Certified Producer’s Certificate, indicating that he has produced the products through the practice of the agricultural arts; only the farmer’s family or direct employees may sell the produce; the certified producer’s certificate must be displayed at the stand; they must use a ‘sealed’ scale; and they can only sell the produce they have raised. Good rules indeed.

Sounds played a prominent part at several points in this year’s symposium, including spontaneous piano renditions of Débussy in the deserted lecture hall by new symposiast Mark Seiden, and the sound of a trumpet leading a chefs’ procession at the final lunch. In the talks themselves, Ashley Young, recipient of this year’s Cherwell Food History Studentship, gave a fascinating account of the cries of street and market vendors in New Orleans and Baltimore, playing actual recordings and even singing along to the cries of “hooorseraadish, hooorseraadish” and “prah – ah – ah – line, prah –ah – li – ine. Anastasia Edwards’ talk on the cries of London fish sellers followed a similar theme, and even included the libretto of a sixteenth-century work by Orlando Gibbons based entirely on such cries LINK.

And that’s not to mention the cry of a modern ferry coming in to an Aegean port – the starting point for a grand hypothesis presented by Andrew Dalby, who argued that the rapid spread of coinage across the Aegean and beyond from its origins in ancient Lydia was because of its usefulness as a medium of exchange in a situation where, just as today, island markets are not regular affairs, but are only set up when a boat, loaded with potential buyers, comes in to port. According to Andrew, THIS is where gastronomy began, and we have to thank people of Asia for the invention of coinage that made the easy purchase of fresh produce possible.

Which was one of the themes in my own presentation with Janet Clarkson, where we acted out the evolution of food markets across the centuries, although our particular emphasis was that the Tragedy of the Commons, where the pursuit of individual ends in a group situation can ultimately lead to disaster, is in fact likely to produce disaster for future food markets, especially in the face of global warming.

Future food markets were the concern of Richard Shepro, who interpreted the present complex long-distance international market as a “giant local market.” Richard’s erudite talk on what freshness now means pointed to the increasing quality of farmed fish, where producers can plan feeding schedules around the expected market (e.g. starving the fish for a fortnight before killing to reduce subsequent spoilage), and box the fish better because their dimensions are predictable. It was slightly alarming, however, to hear of “tuna coffins”, and of fish being transported thousands of miles to market, only to be brought back and sold less than a hundred miles from where they were caught.

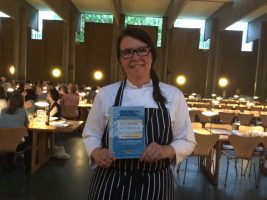

The feeling of the meeting was summed up in Trine Hahnemann’s wonderful talk on the “New Nordic” movement in which she so prominently stars. It is not just about food, although the enthusiasm with which she talked about cooking fresh food (especially vegetables) in innovative new ways found resonance with many in the audience. Her well-reasoned dismissal of some of the technological fast-food “fixes” produced by industrial-scale food manufacturers also found resonance, especially in her important point that this particular technological route “does not demonstrate any understanding of the human need for companionship and for sharing meals.” As a viable alternative, she promoted the message that “locally developed ideas in food are also about creating a market for the exchange of ideas that feed back into the economy and life more generally. … … New Nordic could from this perspective offer a set of ideas and questions about locally grown organic food, and about sustainable development. It helps us answer the question, how do we want to live?” Which is a question that lies at the very heart of the Oxford Symposium itself.

The Food

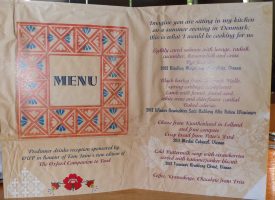

Words could not do justice to the wonderful food that was prepared for the symposiasts by visiting chefs Allegra McEvedy (Friday dinner), Karina Baldry and Katrina Kollegaeva (Saturday lunch), Trine Hahnemann (Saturday dinner) and Joseph Pepe Patricio (Sunday lunch), supported by generous sponsors, supporters and facilitators that included Ursula Heinzelmann, who offered the Friday predinner welcome drinks in celebration of her new book on the history of food in Germany. So instead of words, here are some pictures – the menus, the food, the chefs, the sponsors, and the participants – in short: the symposium.

Photos by: Len Fisher, Aglaia Kremezi & Susan Haddleton

The OSFC warmly thanks the sponsors featured below.

We are very grateful for their generosity.

Plenary Sessions

Keynotes

Darina Allen

Anya von Bremzen

Janet Beizer

Joseph Pepe Patricio

Awardees

OFS Young Chefs

Keelin Tobin

Cherwell Prize

Ashley Young

Meals

Friday Dinner

Market Dinner

Organised by – Elisabeth Luard

Cooked by – Allegra McEvedy and Tim Kelsey & St Catz Staff

Sponsored by – New Covent Garden Market, Maldonado, iberFlavours, Dingley Dell Pork, Food & Wines from Spain, Ultracomida, Riffel, Ubago

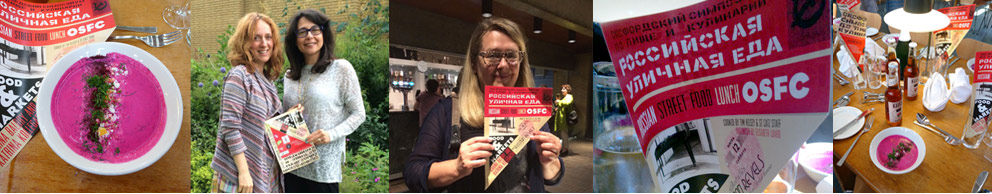

Saturday Lunch

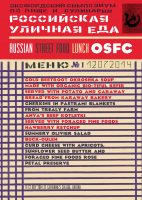

Russian Street Food Lunch

Organised by – Elisabeth Luard

Cooked by – Karina Baldry and Katrina Kollegaeva and Tim Kelsey & St Catz Staff

Sponsored by – Russian Revels, Biotifuldairy, Karaway Bakery, Trealy Farm, Birchgrove, Kvass

Saturday Dinner

Nordic Summer Banquet

Organised by – Elisabeth Luard & Ursula Heinzelmann

Cooked by – Trine Hahnemann and Silla Bjerrum and Tim Kelsey & St Catz Staff

Sponsored by – New Covent Garden Market, Wieninger, Cobenzl, Wien Wein, Mayer, Skaertoft Molle, Knuthenlund, Friis Holm, Weingut Christ, Peters Yard, Loch Duart

Sunday Lunch

Leftover Lunch

Organised by – Elisabeth Luard

Cooked by – Joseph Patricio and Tim Kelsey & St Catz Staff

Sponsored by – Hiver