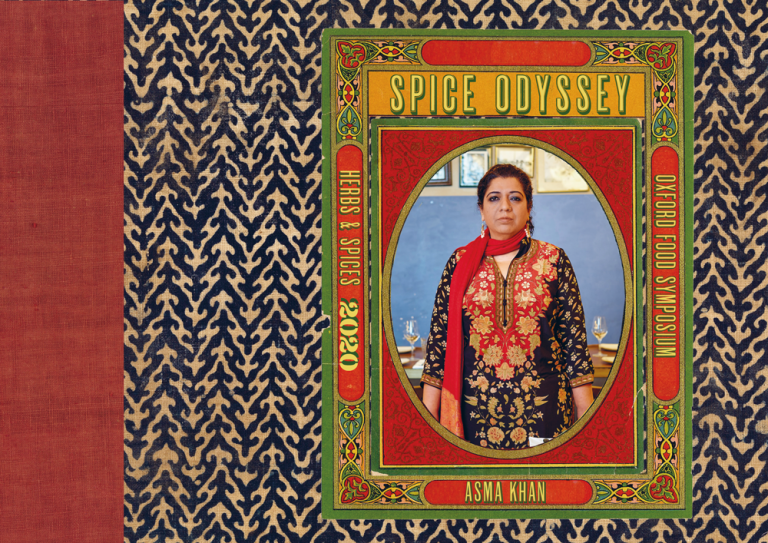

Meet V-Symposium Guest Chef Asma Khan

Symposium Chair Elisabeth Luard talks about life, liberty and food with this year’s guest chef Asma Khan

Asma Khan is a powerhouse for change in the restaurant world. Radical by conviction, royal by descent, Asma’s Darjeeling Express – the title of her book as well as her woman-powered eatery modestly perched on a second-floor balcony overlooking a glittering multi-cultural food-court just off London’s Carnaby Street.

Asma does what she does because she’s educated, entrepreneurial and, most important of all, a woman. That London is the city she lives and works is a tribute to a city she finds extraordinary – tolerant, welcoming, equal and free. No small compliment from a woman whose life’s work is empowering women, particularly those displaced by the wars raging throughout the Middle East.

I first met Asma in person, although I’d long known her by repute, a couple of years ago, when she was hosting a Chanukka supper-club to which I had been invited as a journalist and guest. And found myself – a stroke of luck – opposite the chef-proprietor, unmistakably elegant in her beautiful sari. My notes on the evening say little about the meal – very delicious, it goes without saying – but much about Asma herself. Which is as it should be, considering how influential she is in the world of food.

I was the first girl in my family to go to university. It was thought I wasn’t pretty enough to find a husband. But after university they arranged for me to meet a young man, a lecturer in London, nine years older than me, with a view to marriage. He didn’t know we were being set up and when I told him, he ran away. Immediately. I had to pay the bill. But the next day he came to find me in the office where I worked, and the supervisor came to tell me I had a visitor. I was wearing my work-clothes, terrible shoes. So I went to the balcony and looked over and there he was.

So when we met and could talk properly, it seemed to me that he respected women and would let me do what I wanted without interference. And that’s been so. We have two teenage sons one of whom eats everything and the other won’t eat anything he doesn’t like. My husband’s an academic, so he works through most of the night on his books. Of course he thinks what I do is crazy but he’s proud of me and it works.

Refugee women who come into our kitchen and cook feel empowered – I can see the looks on their faces, the pleasure they take in the memories the women have created together, the happiness on the faces of the people who recognise their mother’s cooking.

I’ve just filmed Chef’s Table for Netflix, and when they wanted the beauty-shots, to show the food all tarted up with foam and flowers, I told them we don’t do that. And so what happened was that all the women who’d cooked with me stood up in a line against a blue wall with their names written beside them. It was wonderful, magnificent. We all felt so proud.

Food is all about power, so of course it’s political. In India, women do all the cooking in the home, clean, care for the children and do all the work that keeps the family together. And yet they’re nameless, thousands of generations of women whose work is unknown, never acknowledged.

Politics in India is divided in just the same way as the social divisions that keep women and men in their place – and as a Muslim in India today, I’d be worried. These days it’s not the maharajahs – Muslim descendants of Muglai dynasties – that hold the power, but the Hindu middle-class, the bureaucrats and businessmen who run the country, supported politically by the rural poor who believe a demagogue will give them what they want. They won’t get it, of course, but that’s not what matters.

The clan is what matters in India – first the family, then the village, then the nation. Women are supposed to be invisible, chattels, brought up to serve the father, then the husband, then the sons.

This is what everywhere needs to change. And I’ve no doubt it will.

“

Battle has already been joined. In an article by Jonathan Nunn in the Guardian in March this year on the reopening of the restaurant trade after the corona-virus lockdown, Asma is quoted as of the opinion that the biggest issue is the need for unionisation. “After this,” she says, “our priority should be to create a powerful union that is the voice of the workers, not the owners and investors.”

Fighting talk. And as you’d expect, Asma’s food is just as delicious and no-nonsense as the woman herself. For recipes and Asma in person, you’ll have to wait for the v-Symposium.

Photo credit Ming Tang-Evans