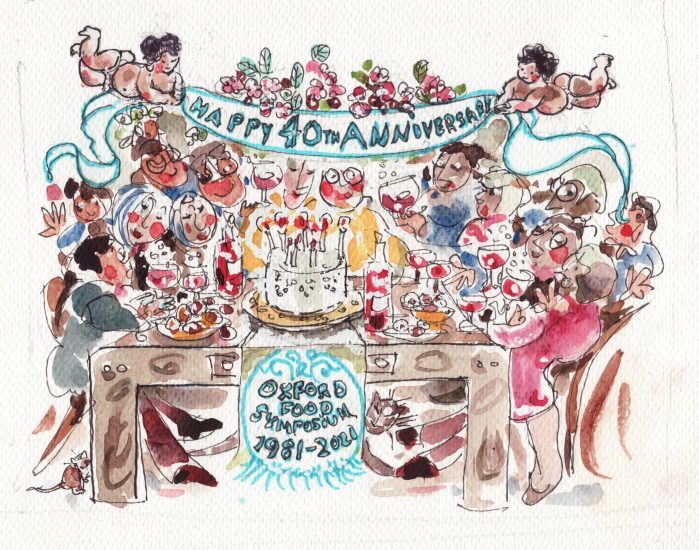

Kitchen Table No. 9 – digest from the chatline

Forty years ago at St. Antony’s College, Oxford, the purpose of what was (and remains) an informal gathering without academic affiliation was the discussion of food & cookery in its historical and modern context. This, though a subject of interest to some twenty people were present at Alan’s suggestion, was not – at Britain’s most venerable University – considered worthy of attention in the groves of academe. Things were about to change. After that first gathering in 1981, the Symposium re-convened in 1983 with a random collection of philosophers, historians, scholars, non-scholars, readers, writers, scientists, biologists and (mostly) subscribers and contributors to the house-journal, Petits Propos Culinaires. Although the morning was spent discussing papers on Food in Motion (a subject we’ll be revisiting as Portable Food in 2022), there was no question that of equal importance was the interaction between participants who would never otherwise meet in person.

From Theodore Zeldin, on who we are:

The whole idea of a Symposium is that everybody must talk. At the beginning, our subject was marginal to the great affairs of the world. Now food is central. In a sense, the need to go on-line has been a coming-of-age for the Symposium. We now know we can contribute to discussions on the environment and everything else, and our voices will be heard. We are no longer just a small charity which interests a couple of hundred eccentrics. The underlying question is how can we make OSFC part of the solution to the many problems our societies face? There’s a lot of power in working in small groups: it can reach people on a deeply personal level. The proliferation of food symposiums all over the world confirms the extent of our intellectual influence – a sign of success. We have made huge progress from where we started. The online Proceedings alone are steadily approaching a million unique users.

From Theodore Zeldin on how we started:

In 1981 the food world, and the rest of the world as such, was very different. We were on the margins. Now we are at the centre of the debate. Alan Davidson’s initial proposal [that food was a subject worthy of study by scientists as well as food-writers and social historians] was completely outside anything the College had ever done. The College was neither interested in Science nor Food. ‘Symposium’ was chosen to assist Alan Davidson in writing his encyclopedia: the idea of a Symposium is that there’s an obligation to contribute to the conversation.

From the chatline and the screen:

What’s most memorable is Alan in his 1923 Bentley that smelt like an old suitcase.

This forum should not shy away from the ‘political’.

Elizabeth David (at the first meeting 1981): ‘If you want to know what people are eating, you must read texts published 25 years afterwards.’

That 25 year measure is a pre-internet timeline; we are probably much faster about memorializing recipes now in cyberspace. Changes in media have had a huge impact on how we eat.

PPC started in 1979, so actually predates the Symposium…

At the first communal meal when everyone was asked to bring something, a sort of anarchy ensued. The bring-your-own meals were a total scrum. One year, everyone was very excited to find out what Julia Child brought but it vanished in seconds. Some things never change.

At the Symposium, you can have a conversation about just about any aspect of food – so different from academic conferences. That’s the beauty of it, you can talk to everyone about anything, which is also true of our virtual symposiums. It’s the [very reverse of] the harmless French tendency to sort things into categories.

I remember with great appreciation ‘An Afghan Meal’ at St Antony’s 15 Sep 2001, just after 9/11. It was a haven of peace.

One of the Nordic ladies – Astrid Riddervold – brought one of the greatest dishes I’ve ever had – gravadlax that had been stored in permafrost. I remember eating fermented whale blubber one year – it smelled and tasted like dirty diapers.

So many of us have been helped by each another. The good that we do spreads out all over the place.

On one occasion, I spoke at length with Alan Davidson about French sea creatures, and then he introduced me to someone else by saying, ‘Meet this chap who just confused a ‘violet’ with a ‘clovisse.’

Charles Perry claimed that his experiments with murri, an Arab condiment prepared with fermented barley flour, attracted neighbourhood cats.

At the beginning, one of the wonderful things about the symposium was that we were so international; we were all like missionaries of the symposium. Following on with the metaphor, sharing food is a secular sacrament.

We received amazing hospitality in Turkey. Alan belly-dancing is unforgettable. Wonderful to know how long that Turkish connection has existed. One of our most valuable Symposiasts was Nevin Halici. Nevin was doing in Turkey what Claudia was doing for Jewish food following the expulsion from Egypt. A never to be forgotten highlight of the 2010 symposium was Aylin Öney Tan’s Yoghurt in the Turkish Kitchen. I kept the dried fermented chunk of yoghurt as a special prize, eked out slowly with grating onto pasta and other foods. It lasted at least a couple of years – the wonder of preservation!

What is coming across so clearly is the degree to which the OSFC has been an amazing group of mutually supportive, like-minded people – like one big family. It has supported and nurtured so much great work. If it didn’t exist, you’d have to invent it!

Ray Sokolov reviewed Thomas Keller when he was only starting out, and put him on the map.

Collegiality and mutual support are an essential part of the culture of the Symposium

Plants [have a central place] in human affairs.

The Symposium has always been a non-academic conference. At the beginning, the food itself was less important, mainly being a bit of an impossibility at the original college. The year 2007 was the first year that the food was really stepped up a level, with several chefs invited to cook with the college. St Catz has allowed the food to go to a different level. Carolin Young and Tim Kelsey transformed the food offering at the Symposium.

The food was absolutely delicious in 2015 – Aglaia’s Greek/Mediterranean contributions and Fabrizia Lanza’s Sicilian dinner. Even 2005—the odd one at Brookes—had an amazing Malaysian wedding feast re-enacted for a lunch.

Does anyone else remember the glorious lunch put together from leftovers of all the previous meals that weekend? So clever.

At St Antony’s one year – maybe the subject was festivals – we brought in tea-lights and put ‘em on all the tables with matches. We nearly got thrown out. Caused an outrage. But the most angry they got was when we gave up on trying to get them to fix the blinds in the lecture theatre and went out and taped loads of black bin liners on to the outside of the building (so as not to disturb the presenters).

Tim Kelsey at Catz has been instrumental in making the food work in ways we couldn’t even dream of in the early 90s. Whereas the chef at St A’s famously told more than one luminary of *&%(! off out of his kitchen.

The chocolate bar for the lunch in honour of Sophie Coe. So much gorgeousness and creativity!

The Pepys dinner by Fergus Henderson organised by Carolin Young and Jane Levi in 2009 in honour of Harlan Walker was the very first menu Jake Tilson made.

The pie Fergus Henderson did for that dinner is still among the tastiest dishes I have ever had! Pie goes straight to the soul. Also the most succulent quail served in big bowls and eaten with our fingers (if we dared).

From Barbara Wheaton: “I wish there were more academically-inclined gatherings that were open like

this in many fields, open-minded and collegial. Knowing that there are things you don’t know is one of the best ways of having adventures. Life is a series of encounters, so each year we have a big dose of encounters. I had to work up courage to be part of the symposium – I was shy. Now the Symposium is the central point about which my world turns.”

From Cathy Kaufman: “It is so true for many of us—it is always the high point of my year!”

From Janet Beizer: “Mine too. And I’ve never met a group of such generous, open, zany (in the best way!) people.”

From Jane Levi: “Alan said there is no qualification. You don’t have to be invited. You can come if you’re interested. And there they all were, these eminent, fascinating, splendid, published people. It was a benign dictatorship between Alan and Theodore. Anarchy sums it up.”

From Harold McGee: “It was thanks to Alan’s generosity I was able to come to the Symposium in 1984 and meet Paul and Theodore and make life-long friendships; and it was this that enabled me to find a British publisher.”

From Jane Levi: “Just remembering another bit of anarchy when I helped Robin Weir wheel a tank of liquid nitrogen into the dining room at St Antony’s so he could make some instant ice cream for the shared lunch… I suddenly start to realise why they were not always our greatest fans. The tank was huge – about a meter and a half high. “

From Malcolm Thick: “My intro to the OFS started in bed one Sunday morning. I read Jane Grigson’s piece in the Observer on Vegetables. I remarked to my wife that Jane’s vegetable history was a bit old-fashioned and she said – write to her. So I did, and she phoned me and arranged a lunch at Shaun Hill’s restaurant in Cricklade. She insisted I write a paper for the Symposium which was only a few weeks away. Unfortunately Jane was too ill to attend the Symposium but she launched me into food history.”

Paul Levy introduced the Young Chef Grants together with Raymond Blanc [in order] to bring theory and practice together.

From Jane Levi: “When Theodore Zeldin and I did our tour of Oxford colleges to find a new home, we knew almost immediately that Catz was the right place because the Bursar was charming and the chef was in the meeting and was thrilled at the idea of meeting and working with our eminent symposiasts.”

From Jessica Seaton: The OFS is the most welcoming group of folk with big hearts and planet-sized brains I’ve ever encountered. That’s the power of food.