Food & Memory: the Personal and the Political – a digest from the chatline

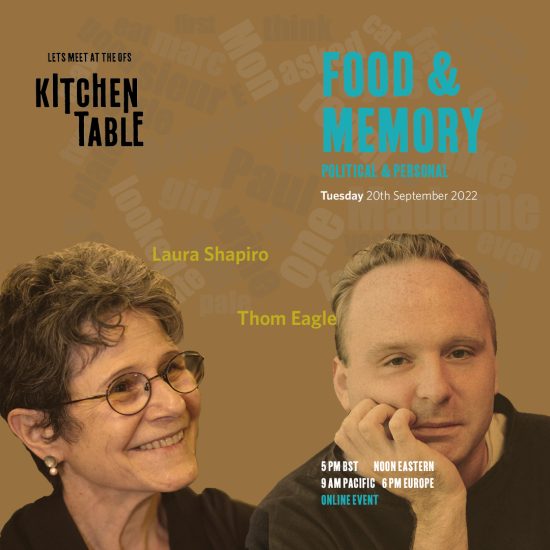

What follows is a digest of the chatline from Food & Memory: the Personal and the Political, a discussion around the Kitchen Table on September 20, 2022, first of the new season. Symposium Chair Cathy Kaufman hosted, culinary historian Laura Shapiro and writer-cook-fermenter Thom Eagle contributed their wisdom and expertise. Attributed quotes (in italics) are interpretations of what was actually said (these informal discussions are not recorded).

RECIPES AS MEMORY-TRIGGERS

Thom: A recipe is the product of a process in the same way as a folk song: a long, layered process over generations.

Recipes are a folk process: everyone remembers some of the words or notes differently and sings them differently. How can a recipe be authentic when it is cooked by many different people? No one cooks the recipe the same way. Recipes are also inventive solutions to problems of scarcity or restrictions or abundance, etc. Claudia Rodenexplains why so many cookery-writers have emigrant status: “we needed to write our recipes down to remember who we are.”

Food is a door opening, a gateway, a wormhole into the past, a conduit to memories embedded in the past. It’s classic Stanislavsky sense-memory. Think about how infants put everything in their mouths as a way to discover what it is. Food comprises so many things, personal/cultural history, social dynamics – Appadurai said “food is a condensed social fact”.

If there are 14 recipe-prototypes and only so many story-prototypes, then creativity happens in the interstices of this slender matrix.

Thom: I didn’t mean to write a memoir with “First Cook…”. I meant to describe the process cooking, but it was inevitable.

COUNTRY VERSUS CITY

Cathy: What is the role of cosmopolitanism in defining a cuisine?

In cities people are bumping up against people who are not like them. Fancy versus fake: it’s such a shame that we can’t appreciate each on its own terms. Isn’t it perhaps also that people like the idea of authenticity? Food doesn’t travel: it’s subject to too many properties of time and place.

Many dishes [we believe to be authentic] have been created from not having all the ingredients – so where’s the ‘authenticity’? Is the assumption that ‘country food’ is the truly authentic stuff, with ‘city food’ being false and fake and second-rate? Isn’t that a kind of xenophobia and possibly racial prejudice? What you get with cities, inevitably, is food that has been influenced by a much wider range of options than those available to the country cook? I agree there’s xenophobia in there, but I believe the ancient Romans also expressed similar attitudes to the food of the countryside/peasant [indicating that country cooking] was more pure than that of the city. So this attitude has some deeper aspects as well. City food is viewed as less “old” or established in comparison to country food being more “authentic”. of something stable.as a “food tradition” . and don’t want to conceive of it as constantly evolving.

Living in Brittany where there is a strong sense of a separate, Celtic heritage, I’ve found there can be a very fine line between celebrating the region’s culture and racism. Cities have always had to import food from the countryside, obvs. New lab-grown has no such limitations. Do we really think that the countryside still uses what is grown there?

AUTHENTICITY (again!)

Laura: Home cooking is always authentic. Restaurant is another country.

The arguments about authenticity are, of course, usually restaurant-focused. Once we start talking about London food, NY food, even appreciatively, isn’t that a way of saying that London isn’t England, New York isn’t America? So Thom’s point about food-fascism [as a way of stifling innovation] is relevent.

Isn’t it [authenticity] personal cuisine as opposed to public – like the memory of the tiny bistro with an elderly lady cooking magical food just for you. There are restaurants and then there are memory palaces. Which got me thinking about how many food “recipes” and processes are handed down orally, without written record. These oral histories metamorphose readily. Also, these oral histories are often personal/familial, but the people who hear them may assume they’re more broadly cultural/historical.

But authenticity and memory are so closely linked, it is what we want or are supposed to remember about things…food…false and acquired memory…selective memory? So what are we really trying to get at when we write a food memoir?

First year of lockdown my sister and I took a subject from our childhood and each wrote our memory of it – interestingly different takes!

I prepared a chili con queso dip that my recently-departed sister used to prepare in the early ‘80s: I wanted to taste a memory of her but sadly it was a bit TOO 1980’s.

MEMORY AND MYTH

Laura: We do eat memory: memory is what gives things flavor. I’ve never written a recipe in my life.

Modern marketing is all about inventing stories. We invent tradition every day. Fake farms, fake narratives, Michael Pollan’s “supermarket pastoral”, engineered ignorance. As consumers we are meant to ignore the story behind our food, which can often be a story of suffering or exploitation of animals or even of food workers.

Indian food bloggers, mostly immigrants or expats, have successfully created memories pieced together from oral traditions and artefacts derived not from their own childhood, or that of their parents who were already urbanites in the 60s and 70’s, to fuel imagined nostalgia. Descriptions of archaic practices and oral traditions plus unsubstantiated stories floating around on the web, have spurred a food revival unprecedented among previous generations of Indian migrants.

We’re in a cultural moment where we are not supposed to remember food-origins, which gets tangled up with authenticity.

Ploughman’s Lunch was originally a Milk Marketing campaign; Pad Thai is a national unification exercise.

A constant search for origins ends up defining a whole group. In Malta, there’s a drive to identify a national cuisine with the result that ‘authentic’ peasant food has been glorified and colonised by the tourist-trade.

Some of my strongest food memories are extremely painful and negative. Food can be weaponized to control esp. children, and to this day I cannot stand the thought of some of the foods I had to eat. The extent to which food memories can be bad is little discussed. In the break-out room, someone remembered opening the fridge to a rank smell and saying “this smells like my first husband!’

What’s interesting is the notion of memory as choice. We create the past we want to remember. Memory helps us decide what to internalise, and what to omit. Then there’s the difference between conscious and unconscious memory. Memory and fantasy are constantly circling each other, especially when we talk about food. Doesn’t memory turn the ordinary into extraordinary?