Alan Davidson and the Symposium’s Turkish connection

Charles Perry pays tribute to the diplomat and food historian Alan Davidson, an incurable romantic who changed the course of food history

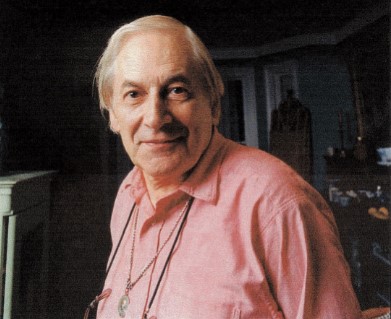

Elisabeth Luard writes: In celebration of our Turkish connection (more than forty-strong at this year’s V-Symp), first-timers and anyone curious to know a little more about our beginnings might like to meet long-time Symposiast and sometime Trustee, Charles Perry, friend for many years of the Symposium’s founding-father, the late Alan Davidson. Their enduring friendship probably had as much to do with a shared view of the world – both men did not always follow the rules – as the study of food-history. As an internationally respected authority on medieval Arabic cookery manuscripts, in 2005, Charles translated the Kitâbu’t-Tabih of Muhammad bin Hasan al-Baghdadi under the title A Baghdad Cookery Book for Prospect Books, the Symposium’s publishing arm. This, however, is not the whole story. Charles’s early life included personal experience of the psychedelic 1960s in San Francisco, eight years as staff-writer on Rolling Stone followed by the publication of a history of Haight-Ashbury. In 1981, Charles attended the first full Oxford Symposium at St. Antony’s, contributing thereafter most years to the published Proceedings. In later years – 1990-2008 – he served as a staff writer for the food section of the Los Angeles Times, and in 1995 he co-founded the Culinary Historians of Southern California.

Our founding-father’s enthusiasm for all things Turkish is recorded in his friend’s affectionate obituary published in the Istanbul-based scholarly journal, Cornucopia, issue 30, 2003/2004.

Alan Davidson was many things: diplomat, novelist, publisher, encyclopedist, patron of the new phenomenon of scholarly food writing…. In all his activities he easily found time to be an influential friend of Turkish cuisine.

There were always at least two sides to Alan. One was the serious, scholarly boy from Leeds who took a double first in Classical Greats at Oxford and went on to be British ambassador to several countries. The other is suggested by a recurring character in the comic stories he wrote at Oxford (one of which was published in Punch in 1948): an eager, incurable romantic, beating his wings against the limitations of the everyday.

In 1962, his American-born wife asked whether he would help her sort out the varieties of fish for sale in the markets of Tunis, mostly unfamiliar, often sold under mysterious Arabic or Greek names. He looked into the matter and realised it would require considerable research, scientific and historical as well as linguistic and culinary: in short, the writing of a novel kind of book about fish.

This challenge seemed to unite his serious and adventurous sides. The resulting pamphlet – later expanded at the urging of the cookery writer Elizabeth David into Mediterranean Seafood (Penguin, 1972) – ultimately led him to turn away from his diplomatic career. In 1975, after the fall of Laos, his last ambassadorial posting, he took early retirement to become a writer, at first specialising in fish.

When I met him in 1980, he had recently taken three epochal steps that would change the course of food history. He had started a small publishing operation, Prospect Books, to reprint historical cookbooks; now headed by his friend Tom Jaine, it has used the slogans “Every volume a brick in the wall of knowledge” and “Each title more arcane than the last”. He had published curious pieces of food writing that could find no home in the commercial press, calling it Petits Propos Culinaires (usually abbreviated to PPC)… And as a fellow of St Antony’s College, he had convened a symposium about cookery and cookery books, which has evolved into an annual event at which unusual food scholarship from all over the world is welcome.

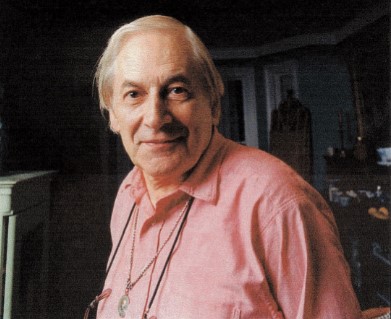

It is through these various activities that he made contact with Turkey. In 1984, the food writer Claudia Roden, a frequent Oxford Symposiast [and now its President], wrote a report for PPC on one of the annual symposiums on Turkish food that Feyzi Halıcı organised in Konya during the 1980s. In 1986, the Davidsons attended Halıcı’s First International Food Congress (Birinci Milletlarası Yemek Kongresi), at which they presented a joint paper on ‘English Perceptions of Turkish Cookery in the 18th and 19th Centuries’.

For Jane Davidson, it was something of a homecoming. The daughter of an American ambassador to Turkey, she had fond memories of glamorous diplomatic balls and romantic outings on the Bosphorus during the 1940s. For Alan, it was a revelation – not only about the quality of Turkish food but the keen intellectual interest the Turks were taking in their culinary heritage. On his return to England, he wrote a glowing report of the congress for PPC, noting the eager coverage the congress received from the Turkish press. (I saw this for myself in 1992, when Turkish television clamoured to interview me about my discovery that some medieval Arab cookbooks included a dish with a Turkish name – karnıyarık – but that it was a pastry, not the stuffed eggplant dish that goes by that name today.)

He also noted the encyclopedic researches on Turkish regional cuisine that were being published by Feyzi Halıcı’s sister, Nevin. The Davidsons, Claudia Roden and their circle were instrumental in bringing her work to the attention of Europe and America, resulting in the publication of her English-language book Nevin Halıcı’s Turkish Cuisine (Dorling Kindersley, 1989). PPC has published a number of articles by Nevin Hanım, and she has attended several Oxford Symposiums.

In 1999, Davidson’s chef d’oeuvre, the project he had been working on since 1976, came to fruition with the publication of The Oxford Companion to Food (OUP), a 1,036-page encyclopedia reflecting his scholarly interests, and also his subtle wit and love of the curious and unexpected. By this time, he had begun to have health problems and consciously started taking steps to ensure that Prospect Books, PPC and the Oxford Symposiums would flourish when he was no longer around. On December 2, he lost consciousness at his home in Chelsea and was rushed to hospital, where he died without awakening. He leaves his wife, Jane, and three daughters.

One consolation his family and his literally countless friends have is that his labours, and his unique role as the centre of a worldwide network of food scholars, had been gloriously recognised the preceding month, when the government of the Netherlands awarded him the prestigious Erasmus Prize.

The prize committee praised him for almost single-handedly elevating the study of food to scholarly respectability. His friends would agree, but to them it seems only part of the purely beneficent influence of his life.

This article appears here by kind permission of author and publisher.