Report By Linda Roodenburg

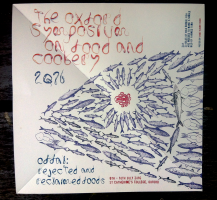

This year was my tenth Symposium. The symposium was fully booked: 220 new and experienced symposiasts from 28 different countries. Among them academics (historians, scientists, art-historians, anthropologists, sociologists, philosophers, linguists), writers and visual artists, chefs, publishers and true amateurs – those who love the subject for itself along. Like many other symposiasts, I have more than one professional life, each with its own symposium, but all pale in comparison with the Oxford Symposium. On offer every year is intense brain-input accompanied by unorthodox meals and tastebud-experiences that surprise even culinary diehards. And which symposium offers such remarkable and good wines? This year’s theme – offal, rejected and reclaimed foods – when taken in the broadest sense is a normative, multi-interpretable subject well-suited to the explorative ethos of the Oxford Symposium not least because there’s no universal agreement on what actually qualifies as offal.

Each culture has its own views on whether foods are acceptable or merit rejection. Even in neighbouring countries, differences run deep. For example, English ‘offal’ is linguistically related to the Dutch word ‘afval’ which means unambiguously ‘garbage’, a designation that includes most animal-intestines and extremities. The negative connotation of the word indicates automatic rejection of offal by the native Dutch. Nevertheless, within the nation, differences can be observed. In modern times, consumption of most varieties of organ-meats, traditionally unusual in The Netherlands, is having a come-back thanks to newcomers from all parts of the world. Goatheads, chickens-feet, blood, liver, testicles, stomach, udder and heart are all available if you know the right butcher.

From post Brexit food politics to cooking with blood

The opening plenary lecture, sponsored by the Jane Grigson Trust, was delivered by Professor Timothy Lang. With a pleasantly suppressed anger he warned the public for post Brexit British food culture: discontinuity in food politics, the danger of lowering food standards, foolish ideas about national self sufficiency and above all the need of shifting from value for money to values for money. As a vegetarian Lang struggled a bit with the theme, but he found his way out by stating that a sustainable diet puts meat into its ecological niche – and if we insist in eating meat, we must eat it all. May be one minor point of criticism on this passionate lecture is that Lang’s talk had some implicit assumptions about our knowledge of English food politics. As an inhabitant of a neighbouring EU country I monitored the voting about Britain’s membership of the EU carefully, but I wondered if our friends from China, Japan and other non-European countries were familiar with the ins and outs of Brexit.

The international focus of the Symposium must certainly not neglect its Oxfordian roots, but it might be a new challenge to look for a balance between the local and the global. In parallel sessions Symposiast were treated to thought-provoking perspectives and information. Among these, a presentation on why huge vegetables can be scary (To Eat an Enormous Sweet Potato, Charity Robey), an inspiring lesson in how to cook with blood (Blood, Not So Simple, Jennifer McLagan), Volker Bach’s Offal and the Art of the Master Cook in Late Medieval and Early Modern Germany, and an elaborate presentation by Suzanne Dunai (recipient of the Cherwell Studentship) on how offal was fully incorporated in Spanish middleclass cooking in the ‘40’s and ‘50’s, just to mention a few of my choices from the rich programme.

On Saturday I chaired a session about offal in three North-European countries. Lenno Munnikes surprised us with Frikandel, the no. 1 Dutch snack: a wasteful or sustainable snack?, followed by Nina Bauer’s Leverpostej—More than just a Danish way of eating offal, and an inventory of offaldishes that used to be cooked in Iceland (Nanna Rögnvaldardóttir: Gone and Forgotten: Hooksteaks, trashbags, and other vanished Icelandic offal dishes). Iceland must have been the world’s offal paradise. Nanna treated us on a home made Icelandic snack.

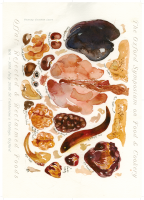

On the first row, Harlan Walker, a highly respected Nestor of the symposium, had his first smoked Icelandic horse tongue (“Delicious!”). And more than ever I admired the coherence of the programme. May be I was lucky in the choices I made, but I think other Symposiasts had the same experience. When in one session ‘cold fat’ was brought up by Sami Zubaida, in a following session Gillian Riley showed the corresponding image on a 16th-Century painting (Offal and Extremities in Art).

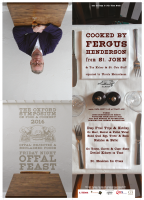

Fergus Henderson’s Friday night feast

The meals, as usual, echoed the theme. On Friday evening chef Fergus Henderson’s dinner was the ideal culinary kick-off. After welcome drinks with book-signing by Elisabeth Luard, we all sat down in the huge dining room where Tim Kelsey and his staff took care of the cooking, the serving and logistics of our meals. Ferguson offered us a wide range of offal dishes, preceded by raw radishes as a counterpart to the coming proteine explosions. (‘Do we have to eat the whole plant?’). Among them: deep fried tripe, ox heart salade, ox tongue and devilled kidneys on toast. There were four nationalities within my hearing range, and at least as many opinions about the dishes. Some of us grew up with organ meat and extremities like trotters and heads, but or others, myself included, the taste is not always successfully acquired.

Oxtailsoup and calf’s tongue were delicacies my mother prepared incidently in the French way, but I never had the real stuff like tripe, lung or testicles at home. And I still don’t. Half of the year I live in France, but I’ll never get used to tripe à la mode de Caën. No wonder I preferred Fergus’ tongue in caper sauce above the kidneys. But my English neighbour loved the kidneys, as a feast of recognition. We all agreed: preparing all parts of the beast is a skill and Fergus Henderson knows how to do it. This culinary adventure ended with a remarkable ice cream. I recognized the bitter flavour of Fernet Branca and realized that alcoholic offal exist as well: my bottle of this dark brown Italian liquor is collecting dust since I brought it from Italy in the ‘80’s.

And there is also a lot of offal in world literature. After dinner Raymond Sokolov and partners read fragments about offal by a.o James Joyce (Ulysses) and Emile Zola (Le Ventre de Paris). In the adjacent room Andrew Dalby and Carolin Young introduced their project Wiki Food and (Mostly) Women.

This important project in collaboration with the British Library improves Wikipedia’s coverage about women and food. (You can join them. See more here.

From Claudia Roden on offal to Paul Rozin on disgust

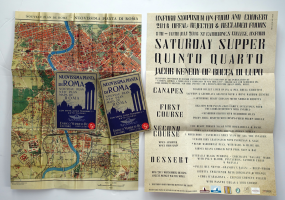

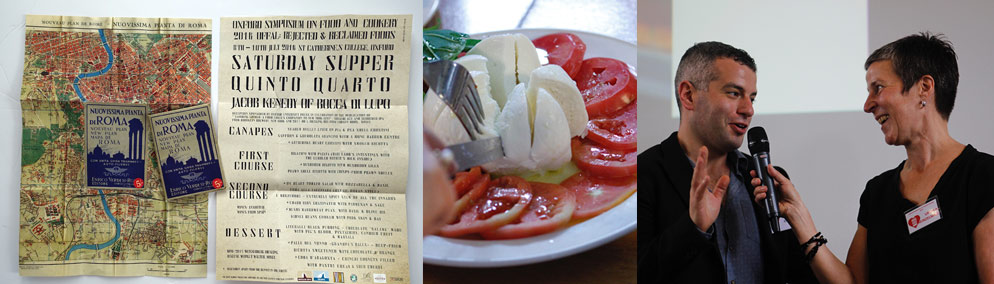

On Saturday, the Symposium’s President, Claudia Roden, expert in world-cuisines, introduced a panel-discussion, The Joy of Offal, with a personal view: “‘There is nowhere disgust of offal. But it does take so long to prepare!” Offal, she continued, is not always considered meat: during Lent and other fast-days, when meat was forbidden by the Roman Catholic Church, organ meat was a permissible foodstuff, explaining the strong presence of offal in old cookbooks and paintings. Anthropologist Merry White introduced the view that ‘offal’ is not a category in Japanese cuisine: only foreigners regard sea-slugs and raw horsemeat as offal. Chef Jacob Kenedy told about his amazing offal-experiences in Sicily and that for the Romans offal is the ‘quinto quarto’ – the fifth quarter – of the animal.

Paul Rozin’s excellent plenary lecture, ‘Disgust and the tasting Menu and some Verse’, addressed the essential elements of disgust. The definition of the word – ‘revulsion at the prospect of oral incorporation of an offensive substance’ – brings the need for a biological perspective. Humans, he explained, are the only species that can enjoy disgust and oral pain. We like the flavours of decay (cheese, fermented fish), the famous Danish restaurant Noma serves life shrimps and ants, and people enjoy the pain of chilli and the bitterness of coffee.

A vegetable offal lunch and a feast of Italian offal

Saturday lunch was rewarding for the vegetarians among us. The London Borough Market and the Oxford Food Bank organized a lunch dedicated to vegetarian offal with ‘left over, rejected, orphaned, and reclaimed’ vegetables.

Vegetarian suffering returned in the evening with Chef Jacob Kenedy of Bocca di Lupo who presented us with quinto quarto dishes from southern Italy. I was sitting next to Yi Ning from Shanghai and wondered how she experienced the Symposium. She works for a consulting company that gives advice to young food-entrepreneurs about innovation and sustainability, so she thought this year’s theme could be very interesting for her.

While she was certainly enjoying the experience, I can imagine, as the Symposium becomes more international, that presenting a paper about a ‘foreign’ cuisine while there are ‘natives’ among your audience could make a presenter a bit nervous. There’s a considerable difference in perspective between growing up in a specific food-culture and analyzing it as an outsider. This posed no problem for Yi, she assured me. On the contrary, she’s interested in all views on her own food-culture and all other cuisines as well. But she had to admit that there’s a gap between what she learned about Chinese cuisine and her own daily meals since she seldom cooks at home and most of her meals come from a take-away.

Liver Divination and In vitro meat

After dinner it was time for the spiritual side of offal. In A Woman Reading a Liver and Other Acts of Divination, Amanda Couch based her intriguing lecture on research on liver-reading as practised in Ancient Greece. She transformed this knowledge to a real liver-reading on the spot. ’Will Andy Murray Win Wimbledon?, a question suggested by the public, wasn’t the most urgent for all spectators (‘Who’s that?’), but the main point was the reading itself, so nobody cared.

Sunday’s plenary lecture by Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft (MIT), The Ends of Offal: Reflections on Laboratory-Grown Meat was based on the idea that technological and moral progress going hand-in-hand is outdated: artificial meat has to deal with moral resistance.

Wurgaft focused on the cultural aspects: before we decide to eat in vitro meat, we must explore the new food-culture it will bring us. No bones, no skin, no offal (or at least not the regular offal) might well be a culinary impoverishment for many of us, but will deliver improvement for the environment since meat-consumption is growing rapidly and meat will, in the future, become impossible to produce and consume as we do today. “A few cells of a cow can turn to 10 tons of meat”, is a quote from Mark Post, the Dutch researcher who sampled the first laboratory-grown hamburger in front of an audience in London in 2013.

On a personal note, Wurgaft also mentioned my favorite cookbook, The In-Vitro Meat Cookbook by Koert van Mensvoort and Hendrik-Jan Grievink, which includes 45 recipes you cannot cook (Dodo nuggets, Cruelty-free pet food, Dinosaur ‘Wing’, Origami Meat, Fried Lab Sweatbreads), an appropriate subject for the Dutch who have long taken a keen interest in food-technology and other ‘improvements’ on nature.

I can just imagine the changing of the landscape when we swap our organic grown meat for in vitro meat!

See you next year at the Oxford Symposium on Food & Landscape!

Plenary Sessions

Keynotes

Timothy Lang

Claudia Roden, Regina Sexton, Merry White, Jacob Kenedy

Paul Rozin

Ben Wurgaft

Peter Hertzmann

Fuchsia Dunlop

Awardees

OFS Young Chefs

Oleg Gref, Joseph Abdelsayed

Cherwell Prize

Suzanne Dunai

Meals

Friday Dinner

Friday night Offal Feast

Cooked by – Fergus Henderson from St. John

Organised by – Ursula Heinzelmann

Sponsored by – Cava brut 1+1=3, Domaine des Chênes, Ultracomida, Quality Meat Scotland, Cru Bourgeois du Médoc

Saturday Lunch

Vegetarian Lunch. Rejected, Orphaned and Reclaimed

Organised by – Borough Market, Oxford Food Bank and Ursula Heinzelmann

Cooked by – Tim Kelsey & St Catz Staff

Sponsored by – Borough Market, Oxford Food Bank, Ted’s Veg, GroCycle, Gourmet Goat, Bread Ahead, Weingut Tinhof, Weingut Reichsgraf von Kesselstatt

Saturday Dinner

Saturday Supper Quinto Quarto

Cooked by – Jacob Kenedy of Bocca di Lupo

Organised by – Caroline Conran

Sponsored by – Brooklyn Brewery, Loosen Bros., Food & Wines From Spain, Weingut Walter/Mosel

Sunday Lunch

Fisherman’s Sunday Lunch

Cooked by – Tim Kelsey & St Catz Staff

Organised by – Elisabeth Luard

Sponsored by – Ultracomida, Domaine de L’Horizon, Weingut Heidi Schröck, Kaeskuche