We need to talk about… Writing Recipes: the Art of Communicating How to Cook – a digest from the chatline

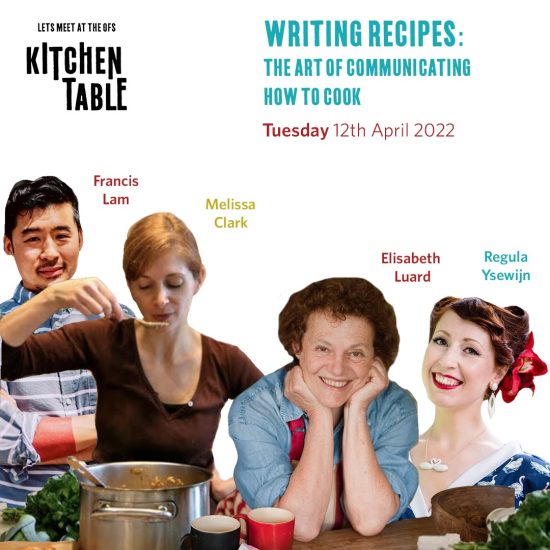

At the Kitchen Table on April 12th, New York Times cookery-columnist Melissa Clark hosted Writing Recipes: The Art of Communicating How to Cook. Joining her at table were Francis Lam, host of The Splendid Table and editor-in-chief at publishers Clarkson Potter; Regula Yswijn, food-writer, photographer and uber-stylist; and OFS chair, writer-illustrator Elisabeth Luard.

THE VALUE OF STORYTELLING

In the US, many people don’t want to cook from the books they buy: they just want to experience them. How many recipes do we [actually] cook from a cookbook? I usually read them because of the stories they tell.

Many of us use cookbooks as points of departure for horizon-widening and mind-opening. I want a guide, not point by point instruction [so that I can] understand enough to adapt to my pantry’s limitations.

Pino Luongo’s A Tuscan in the Kitchen IS evocative and liberating. My favourite books include Patience Gray’sHoney from a Weed – So much teaching and suggesting.

Paul Levy’s point about the distinction between recipes as instruction and recipes as suggestion is so valuable. What Paul is saying about ‘suggestions’ and MK Fisher is entirely true of Elizabeth David as well.

Richard Olney wrote often incredibly long “recipes” that were part recipe, part suggestion, part advice, part commentary. No photos in Olney – but brilliant

Cookbooks for reading can allow a more eccentric structure/organisation: i.e. arranged by main ingredient as in Syrian Canadian Habeeb Salloun’s Arab cooking on a Prairie homestead.

I love cookery books, but rarely follow recipes…inspiration, but not dictating the dish. Because after all, you’re on the own anyhow at some point, because your ingredients will never be exactly the same.

IN DEFENCE OF LONG-FORM

Is there a place today for long-form recipes that are totally impractical – say, start with killing a pig – but tell a story?

Lack of brevity doesn’t necessarily mean assuming the reader has less skill. Length can be to add more precision for experienced cooks in a recipe that’s meant to be precise. Some long recipes are also an example of storytelling.

My guess is recipes started with longer explanations because household cooks were aloneand could not learn from other people around in the same kitchen.

When cooking outside your home traditions, when you’re trying to cook something with which you have no familiarity -you need far more guidance.

Ironic if some long recipes are written to explain what the writer thinks novices need to know, and novices are deterred by the length.

The Tartine bread book has multiple-page recipes – but having read it, it is necessary because it explains both the steps and the why: but it’s hard to read. The Charlie Trotter cookbooks are daunting – but 2-3 pages shouldn’t be a challenge for an ambitious home-cook, especially with sauces and pastries.

With Paula Wolfert’s World of Food, some recipes would take days but it was all worth it. There is a sense of accomplishment in completing a 3-page recipe.

There’s no absolute in recipe writing: you only have to compare Nigel Slater with Delia. And recipe writing is very different from food writing. There used to be a lot more of the latter in magazines and newspapers but now it’s mostly predicated on ‘how to’ stuff.

IN SUPPORT OF BREVITY

At times too much information is as discouraging as too little.

I think one of the factors that made Jamie Oliver such a success story was the shortness of his recipes – sometimes he just pretended they were simple to do and didn’t care about potential questions or problems.

Might a long length somehow convey more authority and credibility — while sometimes making the recipe less practicable?

I wonder if the American style of recipe writing—overly descriptive—tends to make home cooks not trust themselves, rather than the opposite, because they’re literally following directions, rather than understanding the method or riffing on a general idea of a recipe.

ON THE NEED FOR ACCURACY

I’m a scientist, and I love the why. I learned to bake bread with first-time success from Moosewood, as they described how things should feel and look. I still pinch my earlobe to check dough consistency.

Both the Guardian and BBC Good Food have produced series where [a single featured] recipe is examined in the light of other writers’ opinions and methods.

After working in a bakery for a month I realised the recipe is only a small part of the process. The humidity, temperature, starter activity and variability in the flour all plays a lesser or greater role in success or failure. Being able to touch and feel the dough every day was the most valuable lesson to learning.How to convey that tactile feeling on paper?

I have friends who want the recipe to take their hand and guide them 100% the whole way. If you understand the rules then you know how to break them: so if you cook by numbers first, it is a great guide to understand the essence of the recipe and then be more interpretive next time.

Francis Lam says locking in precision through a recipe seemsfaulty. There is no perfection: in the end, you always have to encourage and inspire your reader enough for them to reinvent the dish for themselves.

When I cook with humility, I want to follow a recipe faithfully in order to approximate my existence in a different place. I cook from recipes so I can spend time with someone else in the kitchen.

CHEFS’ COOKBOOKS

A lot of chefs are very poor recipe writers: they assume deep larders and suggest larger quantities than a home cook would use.

The editor’s job is to translate a chef’s recipe. When I edited recipes for a chef at a winery restaurant, the text often seemed like the first time he’d ever written it down. The ingredients and methods didn’t map, there were no timings or quantitiesetc. I had to work hard to clarify with him how the dish could actually get made.

When a magazine made recipes from a local restaurant’s cookbook which they then compared to the restaurant’s offering, the outcome was rarely the same. They also did a sidebar on cost and time – it was a good read.

We all know most chefs’ books are ghosted, but surely thewhole point of restaurant food is that it isn’t home cooking. Even a small professional kitchen will employ three or four people to do the prep. I’d far rather go to the restaurant than try to emulate a dish that is hopelessly complicated for even a proficient home cook.

I’d be curious to hear what publishers are looking for if chefcookbooks are no longer in vogue. I see a lot of cookbooks from social media “influencers” whose recipes (to my mind) aren’t anything special—but they have a large platform/following so publishers know the books will sell.

Melissa Clark made a key point regarding recipes from chefs. I am a chef and in writing a recipe, there is an assumed level of expertise. Chefs cook more by feel, taste, etc. It is hard to distil those tactile pieces of cooking into words on a page. To make a statement that chefs can’t write good recipes is not accurate. The knowledge is in their head, because they do it on a regular basis and have a historical knowledge that they draw on to create a dish or meal.

How do you account for the success of Ottolenghi cook books? They mostly have long lists of ingredients. I have to say I read them (and enjoy the photographs etc) more than I actually cook from them. My cookbook club flipped out over the Ottolenghi recipes – I have not made another book suggestion.

As editors we used to be encouraged to fit a recipe on a page or spread but now it’s quite normal to let a recipe go over a page turn. Working for an American publisher, I had to write every recipe to 450 words – nightmare! Good design can divide out the information – the designer is the unrecognised hero of cookbooks.

Is a recipe supposed to teach you to cook (ie: technique)? Is it for inspiration, or a manual? I am teaching my teen to cookand [seems to me] that technique and cooking are two quite different subject-areas, even though they intersect.

WHAT NEXT?

We really need to get cooking back on the school curriculum so people learn the basics from youth. There’s a petition ongoing in Ireland to get cookery back on the school curriculum. Videos is what got my 10 year old passionate about cooking. He cooks from written recipes, but is inspired by cooking videos by young adults who are cool, which makes it cool for him.

We have a food crisis and an energy crisis and I believe recipe writers and food writers have some responsibility to enable the anxious, busy home cook to feed themselves, friends, family in a sustainable way. I look for more books that convey sustainable eating as joy, not sacrifice. Hopefully books that will do this are in the pipeline.