Kitchen Table No. 6 – digest from the chatline

Tending the Garden : How Microbes Feed Us

Welcome, science nerds et al, to a digest of the gut-friendly chatline from our sixth Kitchen Table co-hosted by Symposium Trustees Jessica Seaton and Carolyn Steel. Given that we happen to live on a geologic spaceship, none better to guide us through the microbial maze than geomorphologist David R. Montgomery and biologist Anne Biklé. Together with the joint authors of The Hidden Half of Nature, we explored the direct (and blindingly obvious) correlation between soil health and human health.

On the importance of healthy soil

The mantra that produces good soil is “moisture, mulch & microbes.”

Roots aren’t fed by soil directly, they’re fed by the microbes that are digesting nutrients.

Think of the soil like a sourdough.

Societies that don’t take care of their soils don’t last.

Plants rooted in soil [produce] a normal, functional, microbial world.

Restoration of the soil can happen quickly, so there’s always hope.

Carbon can be ‘parked’ in the soil.

It’s also interesting to consider what went wrong – when did we start [the kind of] farming that denudes the soil?

What do we know about the nutrient value of food from healthy soil, as compared to food from soil-depleting farming?

Thoughts for farmers and gardeners

A neglected yard is an opportunity.

What’s needed is minimal disturbance of soil and diverse rotation of crops – the earth should be always planted with something.

Living root-cover is like a layer of clover or other nitrogen-rich leafy plants that you then dig in – what gardeners call ‘green manure’.

Growing catch-crops between [rows of cultivated food-plants] helps with insect diversity.

It’s the principles, not the practices, that are transferable – as with biodynamics.

A slash and burn technique is great if there’s endless land, not so good if not.

Once the guano ran out, dependence on chemical fertilisers followed.

Consider how much soil we’ve actually have lost due to land management practices, bearing in mind the obvious commercial incentives for selling intensive monoculture.

There’s interesting work is being done on looking at how nutrients are affected by climate change. It’s possible that higher CO2 makes things grow faster on less nutrition.

Questions could be asked as to whether organic produce in Aldi’s or other discount grocery stores is equal in nutritional value to the organic food you might produce in your garden. The same question can be asked about differences in meat from animals grown on plants raised on different types of soil.

Animals that are pasture-fed are eating phytochemicals, which transfer into the animals’ flesh, leading to deep coloured eggs, golden beef fat, etc

It’s absolutely key that we understand the value of varied-pastured (multiple species of plants) livestock. It’s what we all need to know about how complex (yet simple principles) our food production is.

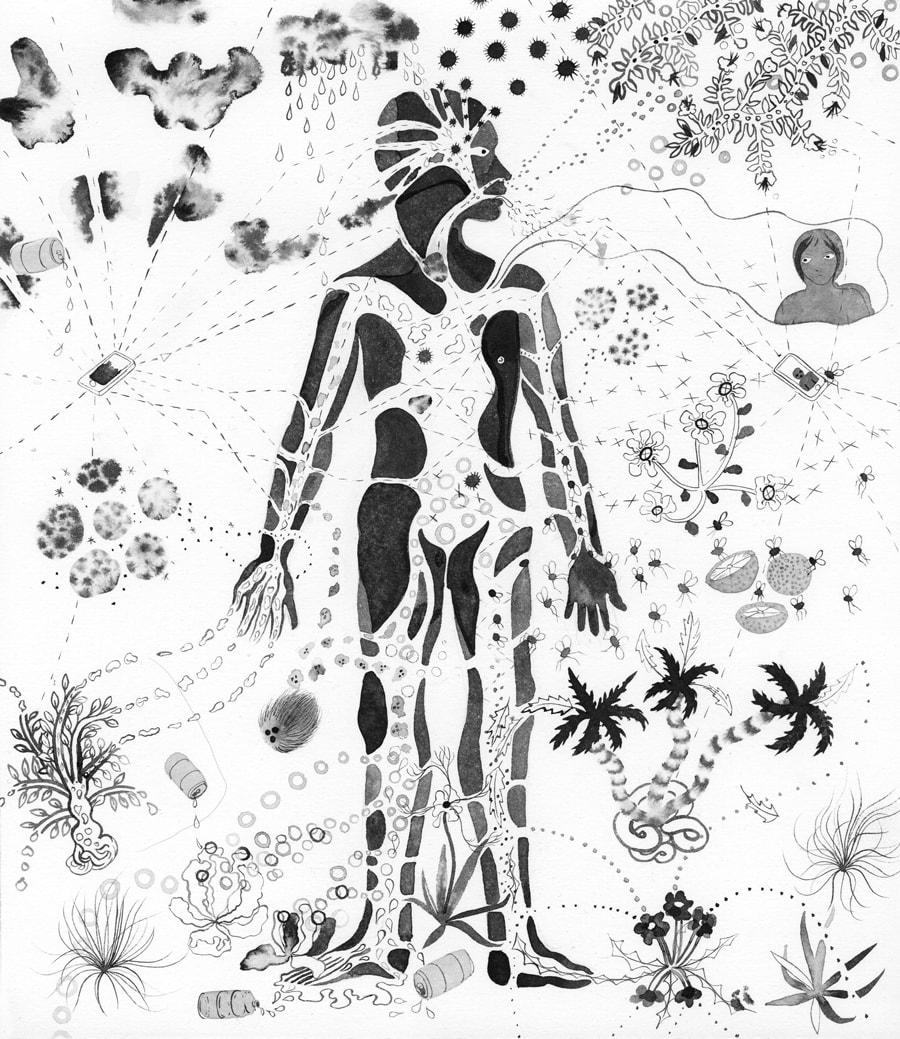

To reach a new understanding, think of your body as a living ecosystem.

Look after your microbes

The human gut is our root system, and when that is functioning well, the rest follows.

A plant-rich diet suits the human gut: when the microbiota eats well, we do well.

There’s communication between gut biota and our endocrine system.

How about describing oneself as a diversivore? Or maybe diversivore climatarians?

You could say that earth is a diversivore, too.

The small creatures [we call] microbes consume nutrients, and then they excrete metabolites, which have medicinal properties in the human body.

We get our microbiome from the external environment. Once it intersects with the human genome it metabolises differently in each of us – which means that the differences between us that make each of us unique, as is each grain of sand, has profound implications for how we eat and how we should be treated medically.

Differences in levels of phytochemicals are dependent on how plants are grown.

Without the microbial world, we have lost the pathways for things to “get in us”.

Determining which phytonutrients each of us need may never be exactly known. Best advice is to eat widely from many plant families, many herbs, spices and so forth, and add something wild every day as it’s much richer in phytonutrients and minerals.

On no-dig farming.

Charles Dowding (the no-dig guru) advises first smothering weeds, and then weeding early to minimise soil disruption.

Allotment gardeners started ‘Digging for Victory’ in the WW2 because people think they have to dig to get rid of weeds.

A semi-wild food-forest may not be popular with neighbours, but it’s biodiverse.

Digging/ploughing delivers short term payoff but long term draw-down.

A couple of centuries ago, London’s market gardens were fertilised with “night soil” – human waste. However, what’s in it now is likely full of drugs, plastic and other industrial chemical metabolites which would need to be broken down before putting on plants. Research is needed on a valuable human resource.

On hydroponics:

When growing in soil, the microbes supply the nutrients; inhydroponics they have to be brought in, which means there’s no contact with the soil microbiome.

The current trend toward mass hydroponic farming in San Francisco has a new major producer,Plenty, which is owned by Amazon. Several years ago the company lobbied hard and were successful to have hydroponics be certified “organic”. The Real Organic Project has been fighting this.

There is so much we don’t know about complexity – hydroponics is simplifying things

We need to ask nutritional and environmental questions about hydroponics.

There’s a half-way situation. Just as there are “wild-caught” fish that are bred in a hatchery, there are plants that are started hydroponically and then moved to soil.

There’s also a less developed field, aeroponics, which actually was designed for space ships.

We need to consider the law of unintended consequences in relation to all these new ways of doing things.

Hydroponics, like cultured “meats”, are also about patents – no such thing as free lunch.