As we get ready to celebrate our 40th year, symposium Chair Elisabeth Luard takes us back to the beginnings of OSFC

Wind the clock back forty years to 1981. Assembled at St Antony’s College, Oxford, is random collection of philosophers, historians, scholars, non-scholars, readers, writers, scientists, biologists and (mostly) subscribers and contributors to Petits Propos Culinaires, house-journal of the gathering. The purpose is the discussion of food & cookery in its historical and modern context, a subject of interest to all present but not – at Britain’s most venerable University – considered worthy of the groves of academe.

Right. It’s a sunny day under the dreaming spires – in memory, isn’t it always? – and the Symposiasts (chosen designation of the group) are dispersed about the lawn and on the steps of the college’s 1950’s buildings, eating their bring-your-own lunch (buried salmon, chocolate-covered garlic) and chatting. Although the morning has seen the presentation of papers on Food in Motion (a subject we’ll be revisiting as Portable Food in 2022), there’s no question that of equal importance is the interaction between participants from around the globe who would never otherwise meet in person.

Appropriate to the diversity of the gathering is St. Antony’s reputation for eccentricity. Rumour has it – always denied but re-surfacing for the joy of it – that the college is (or was) a retirement home for the shadowy intellectuals of the British secret service (and possibly a few renegade Russians). Symposium co-founder Theodore Zeldin, distinguished historian of all things French, remains in place.

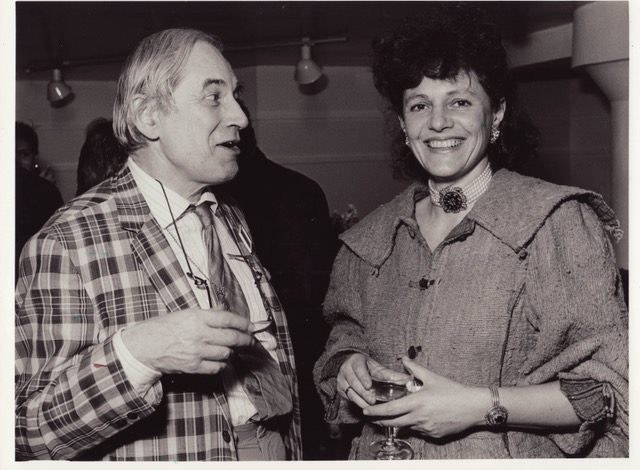

I came a little late to the party, three years after that first official Symposium, as a fledging food-writer with an earlier career as a natural history artist, at the suggestion of Alan Davidson after I’d tracked him to his book-stuffed basement-office in Chelsea. At the time, 1984, I was stitching together the raw material of my first book, European Peasant Cookery, and planning to spend a respectable publisher’s advance on travels in the regions with which I wasn’t already familiar – Eastern Europe and Scandinavia.

“You’ll meet people who can help you,” was Alan’s advice.

And it was true. Astri Riddervold of Oslo sent me to north of the Arctic Circle to visit her daughter who’d married a farmer and lived in the old way, where the land was cropped vertically from shore to hill-top. Max Lake gave me insights into the function of smell and taste as a marker of regional identity, Sami Zubeida provided an overview of the Ottoman Empire that dictated the limits of my research in Eastern Europe. Ray Sokolov set everyone straight on the real story behind nouvelle cuisine: forget Michel Guérard, purveyor of slimming diets to my gourmet granddad (among others), blame it on Fernand Point and Paul Bocuse.

From that time onwards I was hooked. I was back again in 1985 when – as Paul Levy recorded in “Out to Lunch”, a collection of essays from his time as food-editor of The Observer – Harold McGee explained the science behind why mayonnaise splits, Bruce Kraig suggested (outrageously) that eating dog by pet-lovers could be considered cannibalism, Claudia Roden shared her research on early Islamic cookery manuscripts and Alicia Rios performed an exorcism involving garlic-cloves washed down from a flaming bowlful of neat alcohol. And I was there at Oxford Brooks in 2004 when foraging guru Roger Phillips addressed us on wild food, and again in 2006 for the transition to St. Catz, our home from home.

Forty years on, gastronomic revelations still come thick and fast. Meanwhile, I’ve good reason to be grateful for the generosity of my fellow Symposiasts in sharing what they know. This year, as last, when we’re obliged to come together virtually, there’s no doubt that the spirit of openness and willingness to learn remains unchanged.